The Art Of Beatrix Potter: Sketches, Paintings, and Illustrations (Chronicle Books, 2016)

I never read Beatrix Potter (I read Ladybird books, A. A. Milne’s poems, and The Wind In The Willows), but like everyone else, I grew up knowing her name. A recent book on the author-illustrator’s work has given me a grown-up appreciation of her talents as an artist. She got her start in greeting cards, which necessarily reward the capacity to work small. I get the sense that, had I known her, we would have got on: she is fascinated by the smaller wildlife, including fungi, which she often painted; no animal is too small or unglamorous to be of interest; the countryside in different seasons inspired her to paint; and she also has some lovely interior scenes. I love her handling of colour, her unfussy yet instantly legible forms, her ability to unify a scene with colour and proportion (nothing too dominant when it shouldn’t be). Her work is like a cake well done: just the right balance of elements, not too rich, not too sweet — but with plenty of flavour. Her use of ink with watercolours is perhaps the icing on that cake — or shall we say, more essential, like the almonds on a Dundee?

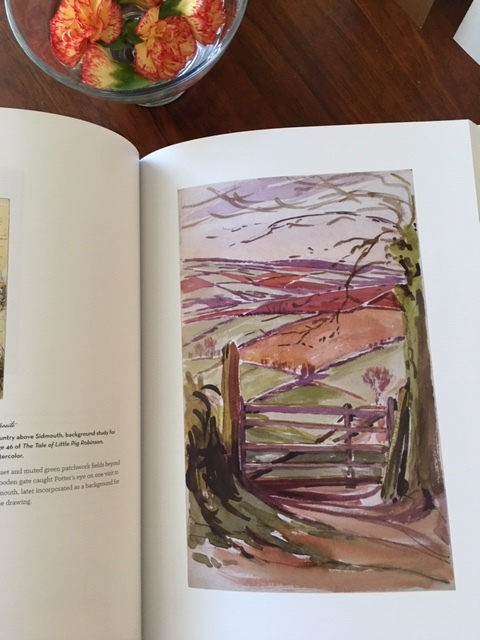

Pictures from the book, left to right: the country above Sidmouth, a study for The Tales of Pig Robinson; an unfinished painting of Melford Hall (1903), and an earlier painting of guinea pigs for an unpublished greeting card.